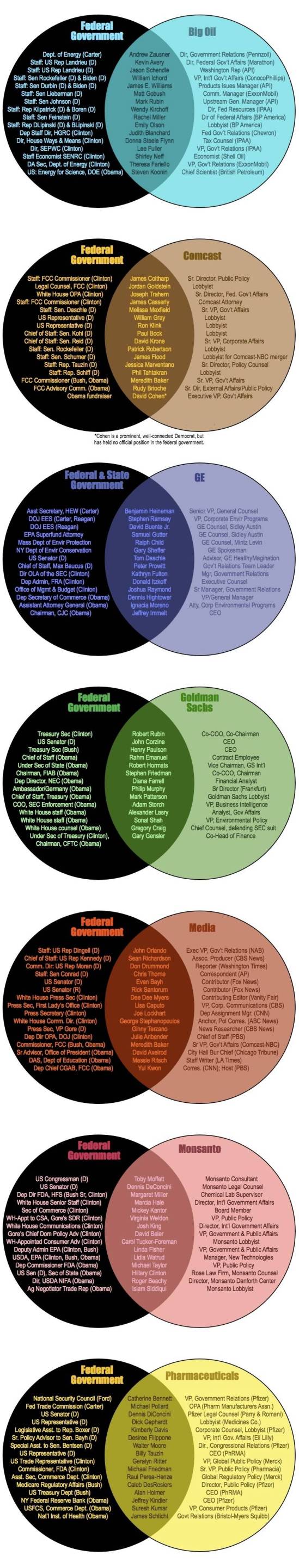

Looking at the agencies, businesses and government and how porous these groups are, it is not hard to see why our government is unable to make decisions unaffected by lobbyists and special interests. Many of these charts show government officials who move back and forth between the government and leadership roles in corporations with special interests or seeking to craft laws to benefit the corporations in question. Here is an excerpt from Public Citizen, an agency concerned with the revolving door between government and private enterprise and the potential conflict of interests:

“Revolving Door” Restrictions on Federal Employees Becoming Lobbyists

“Revolving door” is a term commonly used to describe a potentially corrupting interrelationship between the private sector and public service. The term is used to describe three distinct transitions for individuals between the private sector and public service:

-

The Government-to-Lobbyist Revolving Door, through which former lawmakers and government employees use their inside connections and knowledge to advance the policy and regulatory interests of their industry clients.

-

The Government-to-Industry Revolving Door, through which public officials move to lucrative private sector roles from which they can use their public service and experience to compromise government procurement contracts and regulatory policy.

-

The Industry-to-Government “Reverse” Revolving Door, through which the appointment of industry leaders and employees to key posts in federal agencies may establish a pro-business bias in policy formulation and regulatory enforcement.

Each of these types of revolving door situations is subject to different statutory and regulatory restrictions.

This fact sheet discusses regulation of the government-to-lobbyist revolving door, which first took shape at the federal level with the Ethics in Government Act of 1978. This law called for a “cooling off” period between retiring as a senior governmental employee in the executive branch of government and representing private interests before executive agencies as a lobbyist. The cooling off period was expanded to include members of Congress and senior congressional staff about a decade later in the Ethics Reform Act of 1989.

Since that time additional statutory and regulatory constraints have addressed some of the problems and abuses associated with the government-to-lobbyist revolving door. These include conflict of interest restrictions on negotiating future employment while serving as a public official, lobbying on legislation in which the former public official played a substantial role in shaping, representing foreign interests and governments, as well as the cooling off period. Although there are similarities of revolving door restrictions applying to officers and employees of the Senate, the House and the executive branch, these restrictions do vary significantly between the two branches of government and the level of government service.

The revolving door of former government officials-turned-lobbyists raises at least two serious ethical concerns:

-

The revolving door can cast significant doubt on the integrity of official actions and legislation. A Member of Congress or a government employee could well be influenced in their official actions by promises of high-paying jobs in the private sector from a business that has a pecuniary interest in the official’s actions while in government.

-

Former government officials turned lobbyists bring with them special attributes developed while working as a public servant. They typically have developed a closed network of friends and colleagues still in government service that they can tap on behalf of their paying clients as well as insider knowledge of legislators and public officials, legislation and the legislative process not available to others. In effect, former officials can “cash in” on their experience as a public servant.

In order to minimize abuses, federal revolving door policies attempt to address both of these concerns: Reducing the conflict of interests that may arise in negotiating future employment while a public employee; and limiting the lobbying activities of former officials for a specified period of time after leaving public office.

Negotiating Future Employment

Conflict of interest laws and regulations governing when and how public officials may seek future employment are very different between the executive branches and Congress. These different restrictions are as follows:

- Executive Branch Officials and Employees

- Officers and employees in the executive branch, are generally prohibited from seeking future employment and working on official acts simultaneously, if the official actions may be of significant benefit to the potential employer.[1]

- Waivers may be granted to this prohibition for a number of reasons, as when the employee’s self-interest is “not so substantial” as to affect the integrity of services provided by the employee, or if the need for the employee’s services outweighs the potential for a conflict of interest, according to federal regulations.[2]

- The granting of waivers is the responsibility of the director of each executive agency, though the Office of Governmental Ethics (OGE) – the agency that oversees the code of ethics for the executive branch – offers guidelines for waivers.[3]

- Because of inconsistencies in the standards for granting waivers, President Bush issued an executive order on January 6, 2004, requiring that agencies first consult with the White House Office of General Counsel. Waivers are not formally public record, unless requested through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).[4]

2. Congressional Officials and Employees

Other than anti-bribery laws, for members of Congress and their staff:

- No conflict of interest statute exists, similar to the executive branch, regulating negotiations of future employment.

- Rules are described in the House and Senate code of ethics, which prohibit members and staff from receiving compensation “by virtue of influence improperly exerted” from their official positions.

- The rules advise members and staff to recuse themselves from official actions of interest to a prospective employer while job negotiations are underway and for members to seek prior approval from the ethics committee about conducting such job negotiations. However, recusal is not mandatory and there is no system of waivers or public disclosure of these potential conflicts of interest.[5]

Post-Government “Cooling Off” Period

Under criminal statutes, Members of Congress and the employees of both the executive and legislative branches of the federal government are subject to restrictions on post-government lobbying activities.[6] These restrictions include:

- One year “cooling-off” period on lobbying. Generally, former Members of Congress and senior level staff of both the executive and legislative branches are prohibited from making direct lobbying contacts with former colleagues for one year after leaving public service. Specifically:

- Former members of Congress may not directly communicate with any member, officer or employee of either house of Congress with the intent to influence official action.

- Senior congressional staff (having made at least 75 percent of a member’s salary) may not make direct lobbying contacts with members of Congress they served, or the members and staff of legislative committees or offices in which they served.

- Former members of Congress and senior staff also may not represent, aid or advise a foreign government or foreign political party with the intent to influence a decision by any federal official in the executive or legislative branches.

- “Very senior” staff of the executive branch, classified according to salary ranges, are prohibited from making direct lobbying contacts with any political appointee in the executive branch.

- “Senior” staff of the executive branch, those previously paid at Executive Schedule V and up, are prohibited from making direct lobbying contacts with their former agency or on behalf of a foreign government or foreign political party.

- Any former governmental employee, regardless of previous salary, may not use confidential information obtained by means of personal and substantial participation in trade or treaty negotiations in representing, aiding or advising anyone other than the United States regarding those negotiations.

- Two-year ban on “switching sides” by supervisory staff of the executive branch. Senior staff in the executive branch who served in a supervisory role over an official matter that involved a specific party, such as a government contract, may not make lobbying contacts on the same matter with executive agencies for two years after leaving public service.

- Life-time ban on “switching sides” by executive branch personnel substantially and personally involved in the matter. Senior staff in the executive branch who were substantially and personally involved in an official matter that involved a specific party, such as a government contract, are permanently prohibited from making lobbying contacts on the same matter with executive agencies.

The “cooling off” period applies only to making lobbying contacts with the restricted government agencies or personnel. As a result, a former public official or former senior government employee may research relevant issues, develop lobbying strategies and supervise those lobbying their former agencies or personnel immediately upon leaving office, so long as the former official does not make the actual lobbying contact during the cooling off period. The former official simply directs other lobbyists to make the contact.

July 25, 2005

Endnotes

Pingback: America, Fucked Yeah! | A Matter of Scale